Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Statistics: 2024 Update

Report Highlights

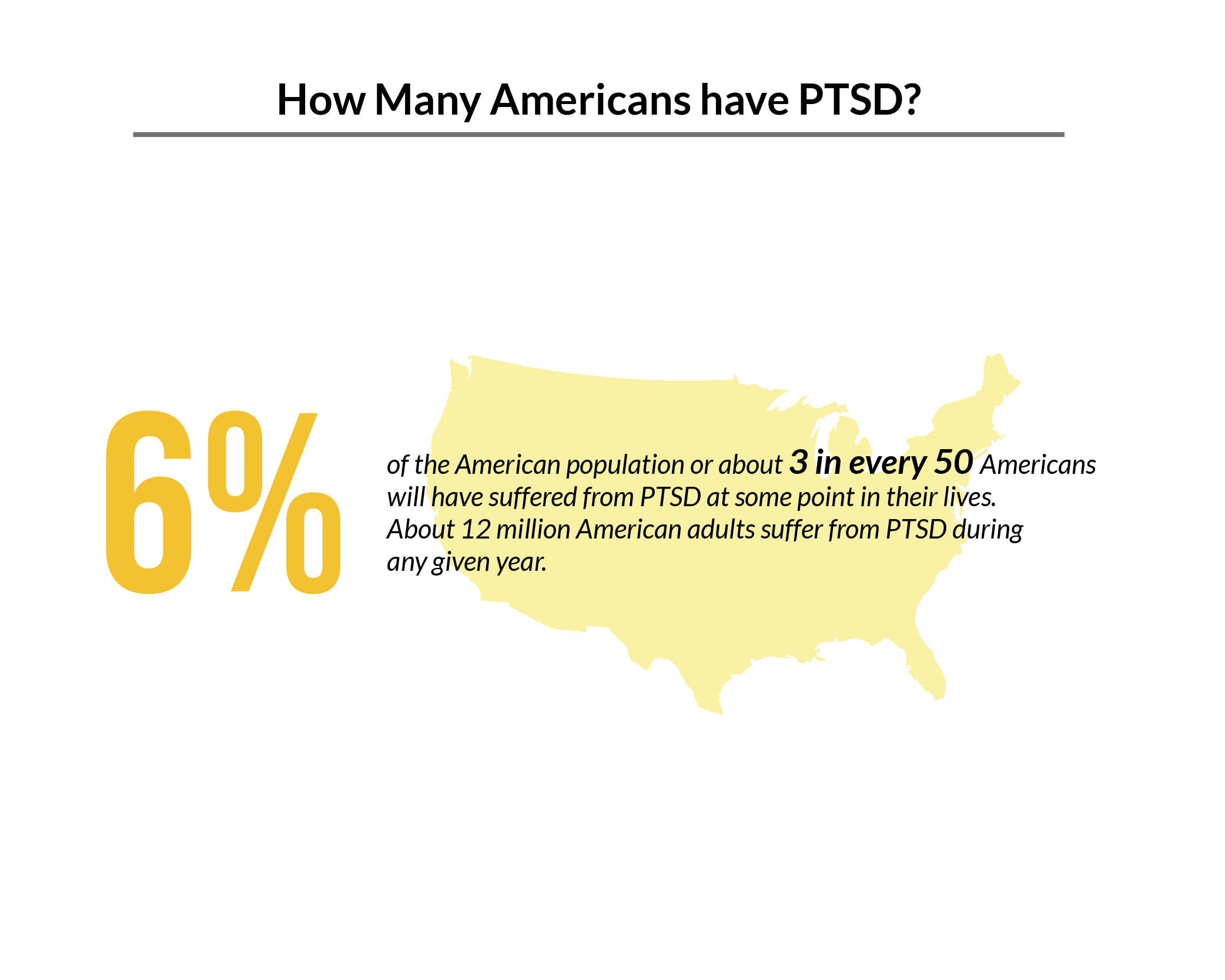

- 6% or 3 in every 50 American adults will have gone through PTSD or post-traumatic stress disorder at some point in their lives [9].

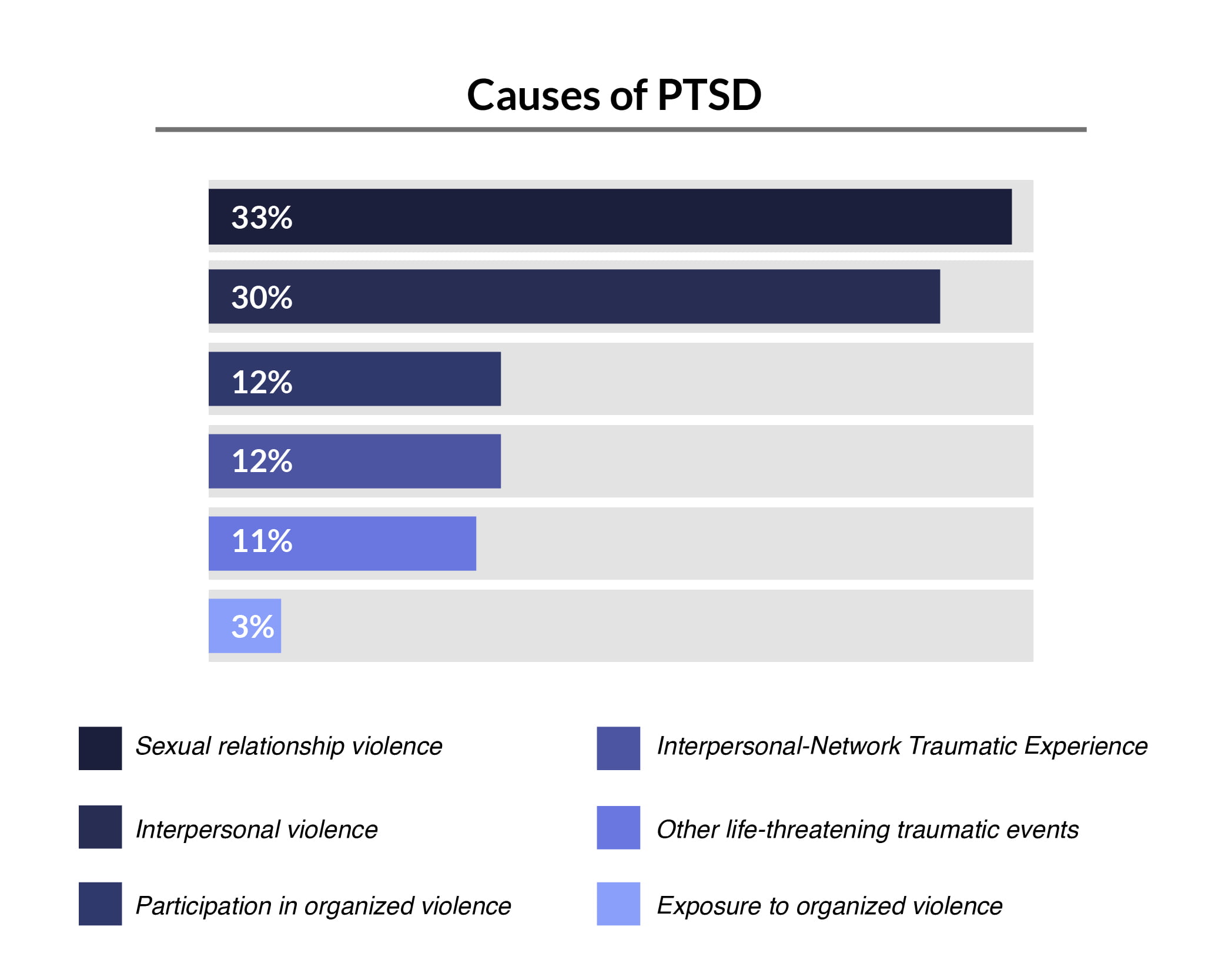

- The leading cause of PTSD is sexual violence at 33%, with 94% of rape victims developing symptoms of PTSD during the first two weeks after their traumatic experience [23] [28].

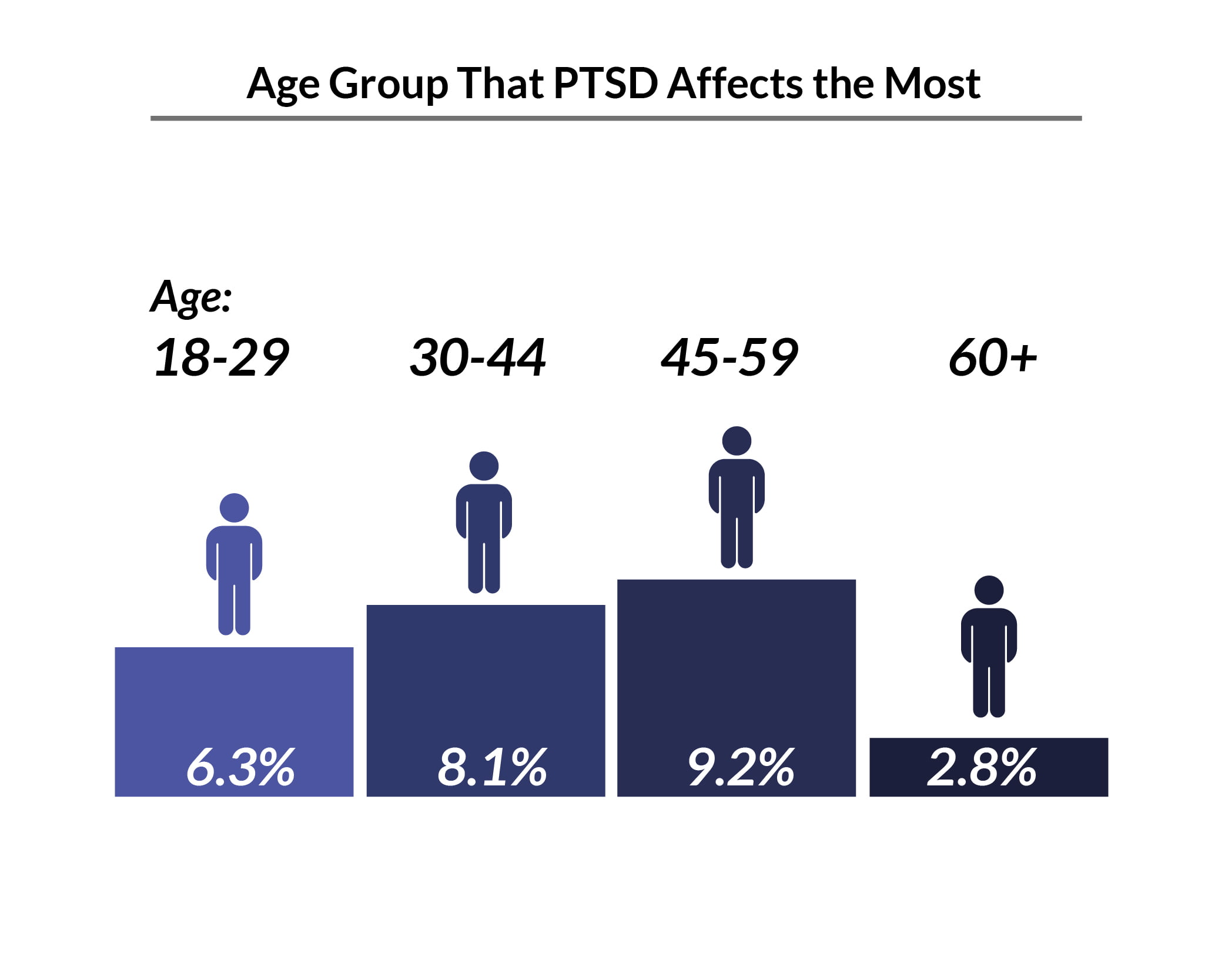

- PTSD is most prevalent among American adults between the ages of 45 and 49 years old at 9.2% [12].

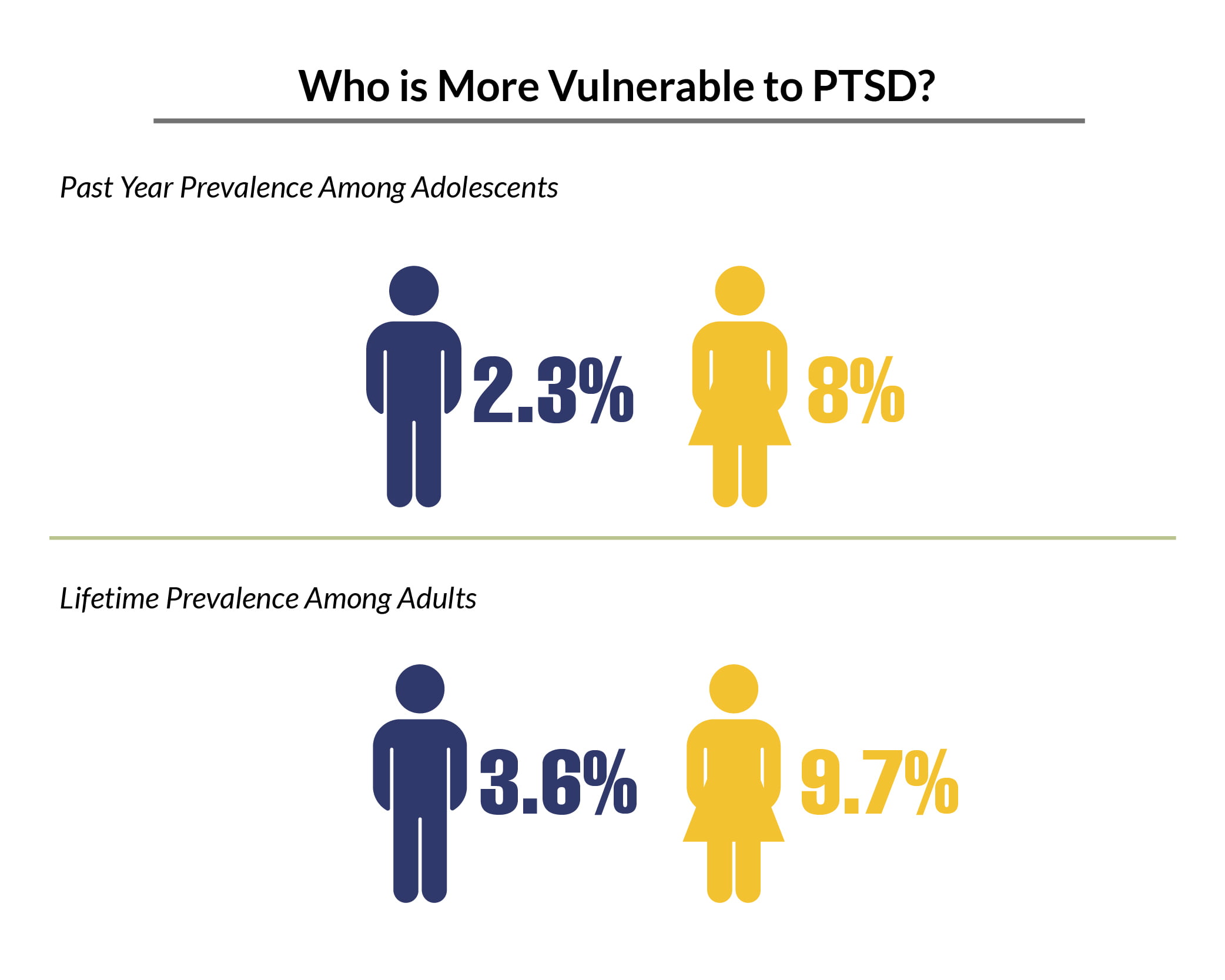

- Women have a lifetime PTSD prevalence rate of 9.7%, compared to 3.6% in men [17].

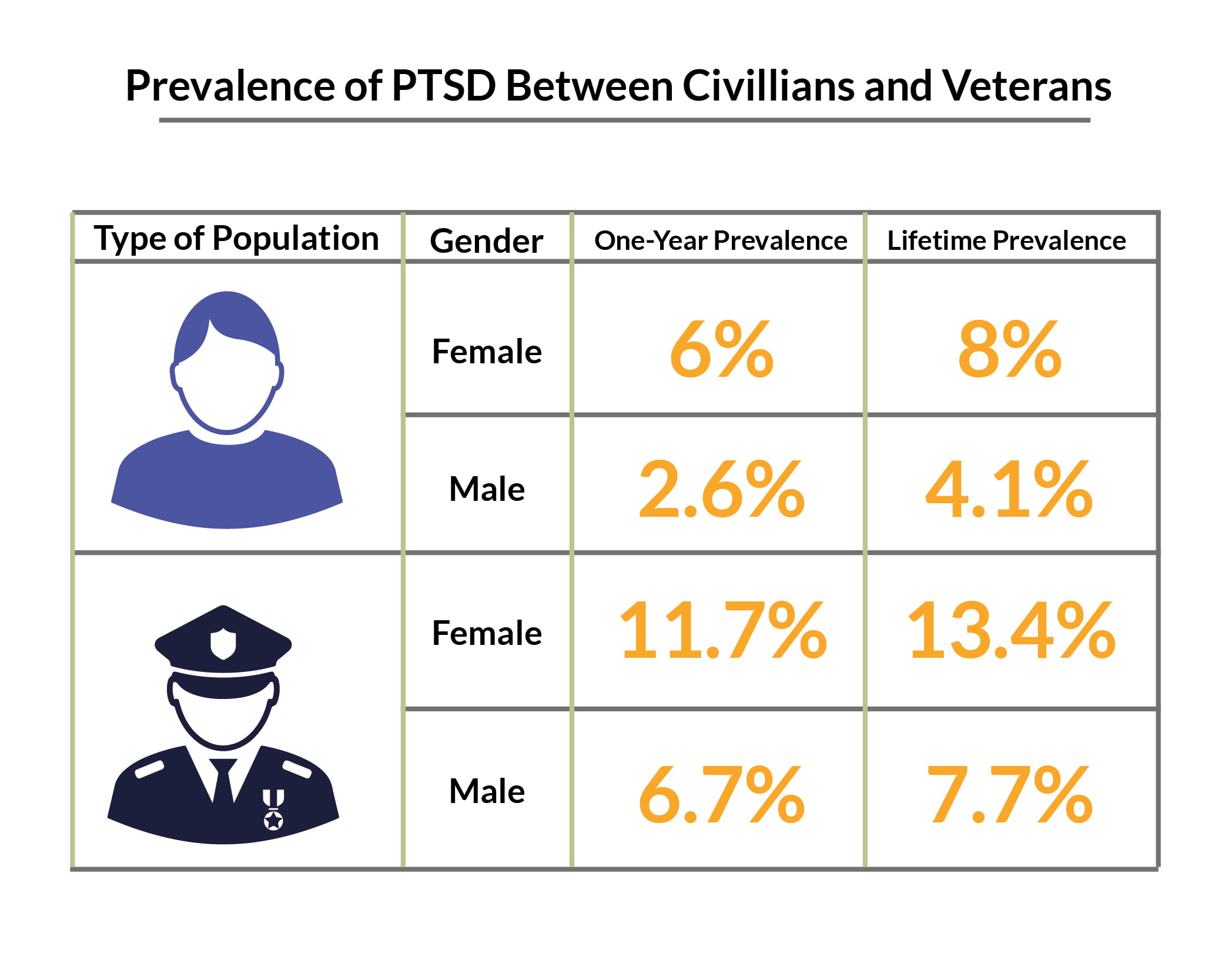

- Civilian women have a lifetime prevalence rate of 8%, compared to 13.4% among military women [24].

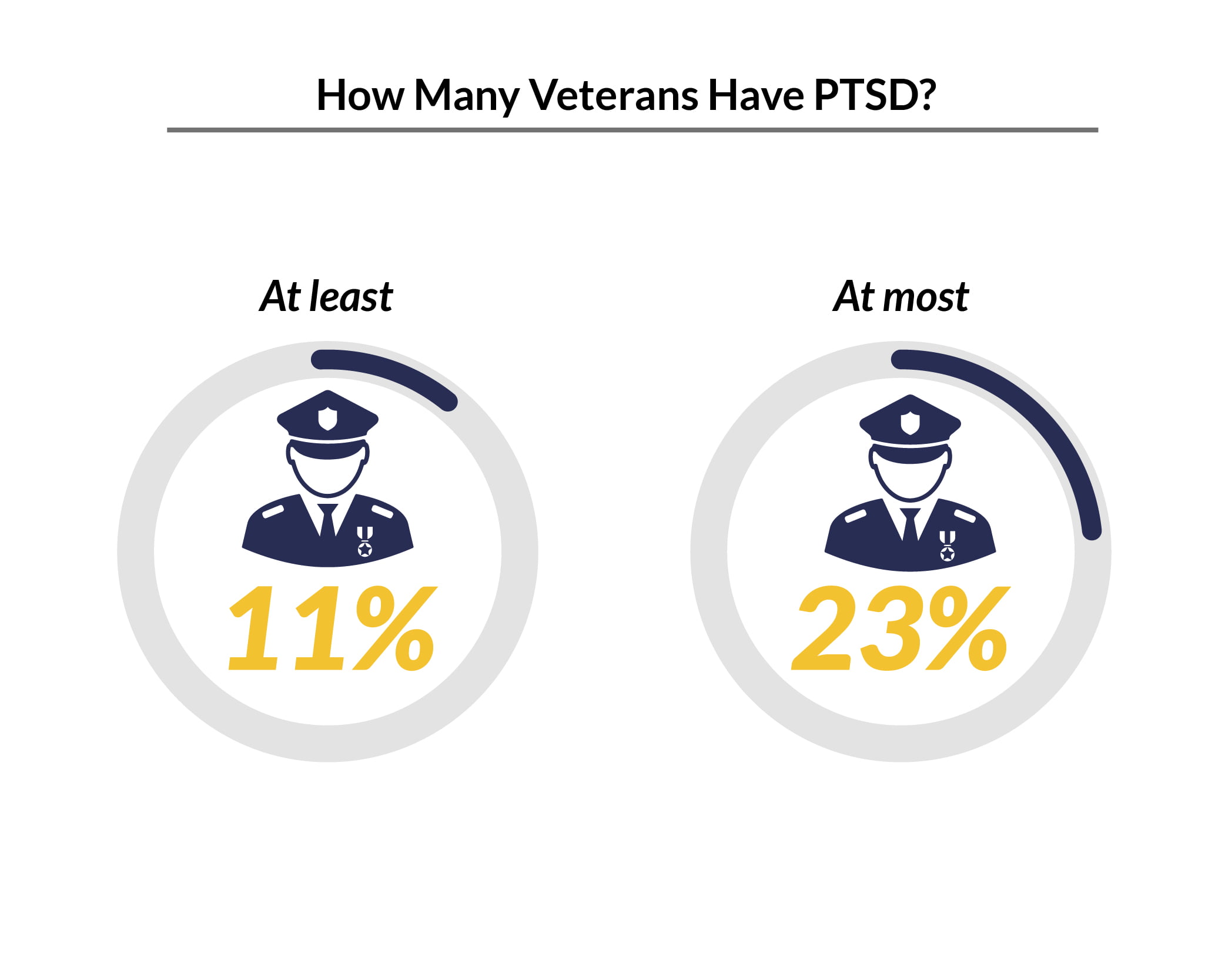

- 11% to 23% of veterans have experienced PTSD within a given year [2].

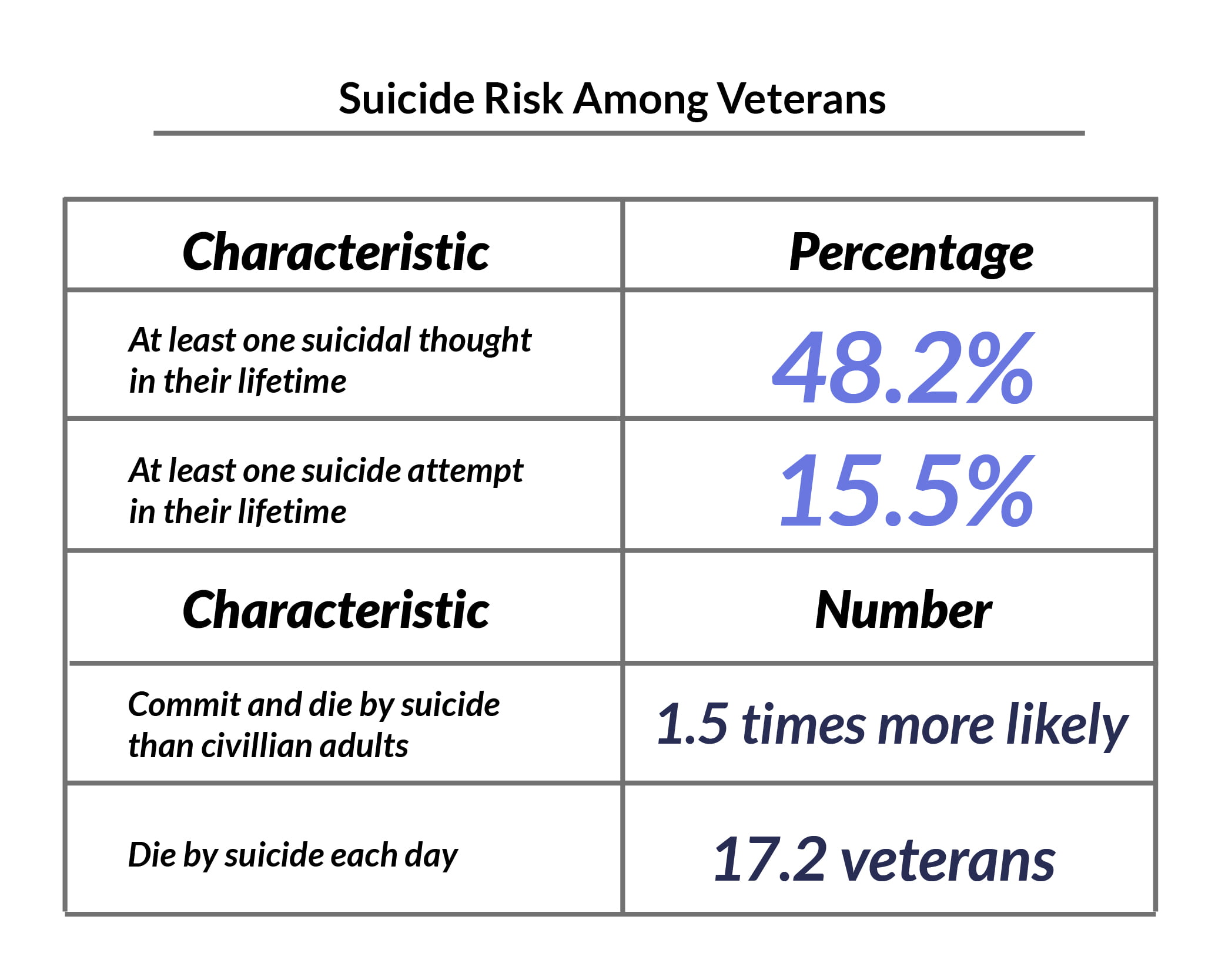

- About 17.2 veterans die by suicide each day, with veterans being 1.5 times more likely to die by suicide than civilians [2].

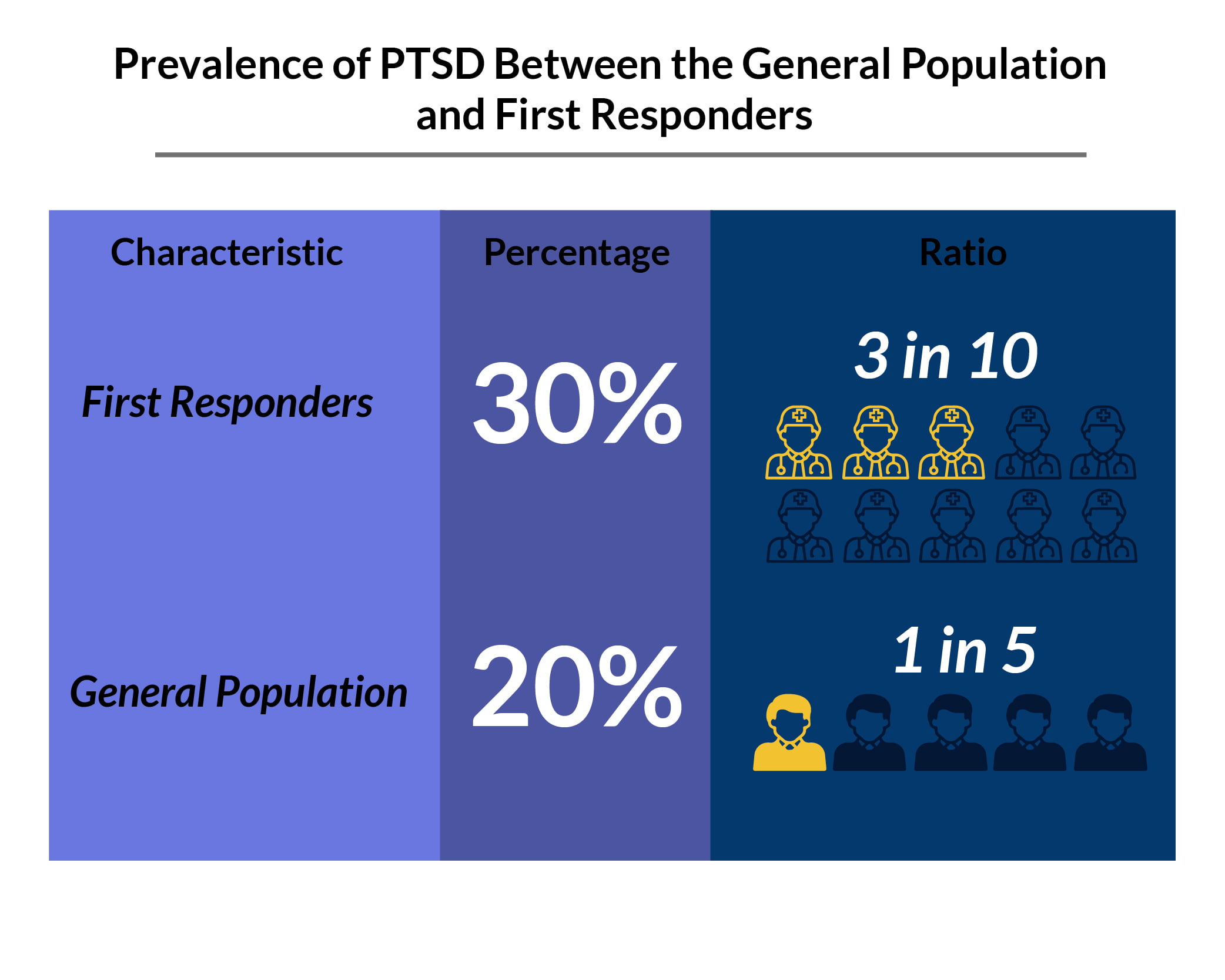

- 3 in 10 or 30% of the first responders have PTSD [6].

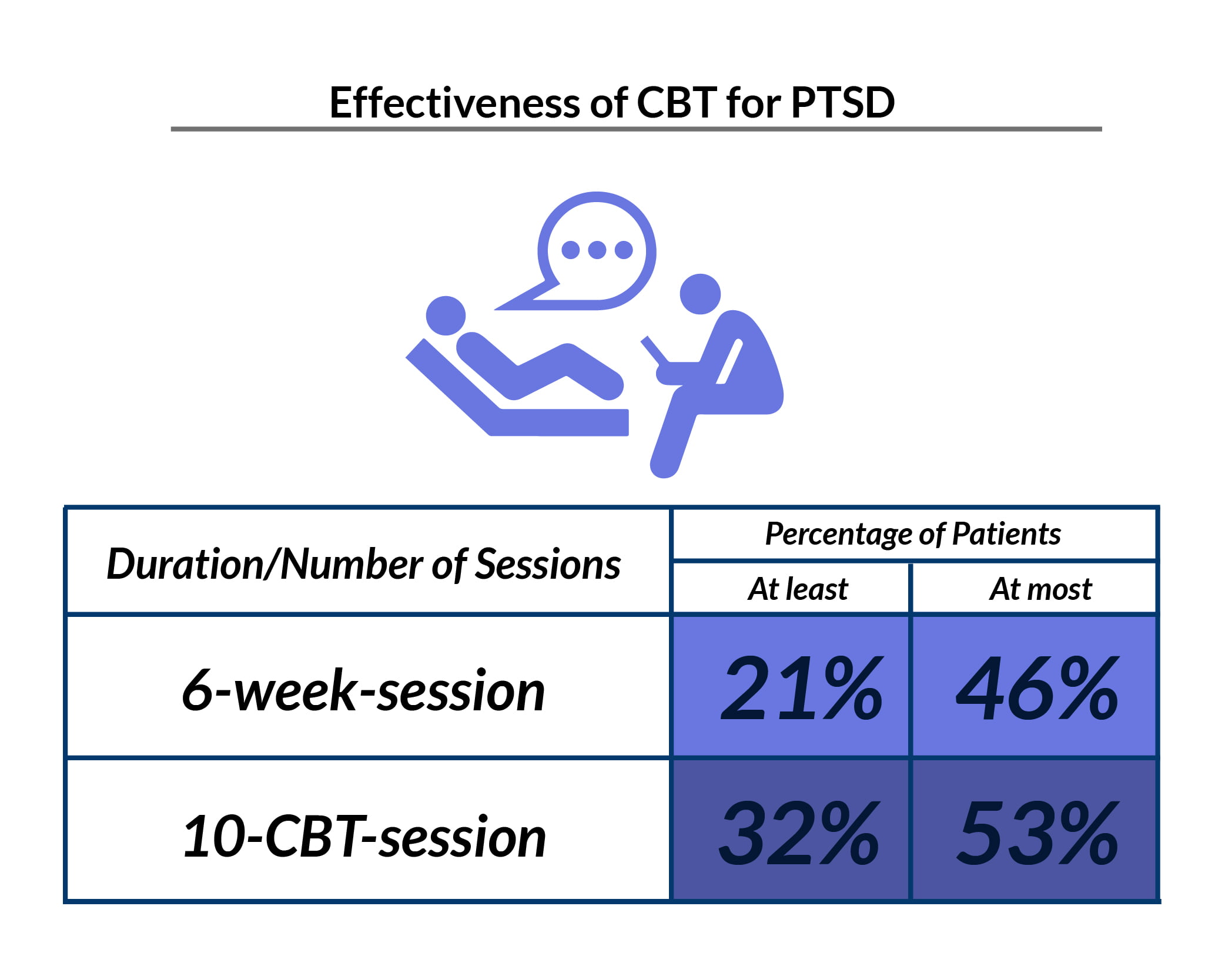

- 6 weeks of cognitive behavioral therapy can help ease symptom severity by about 50% in 21% to 46% of patients with PTSD [7].

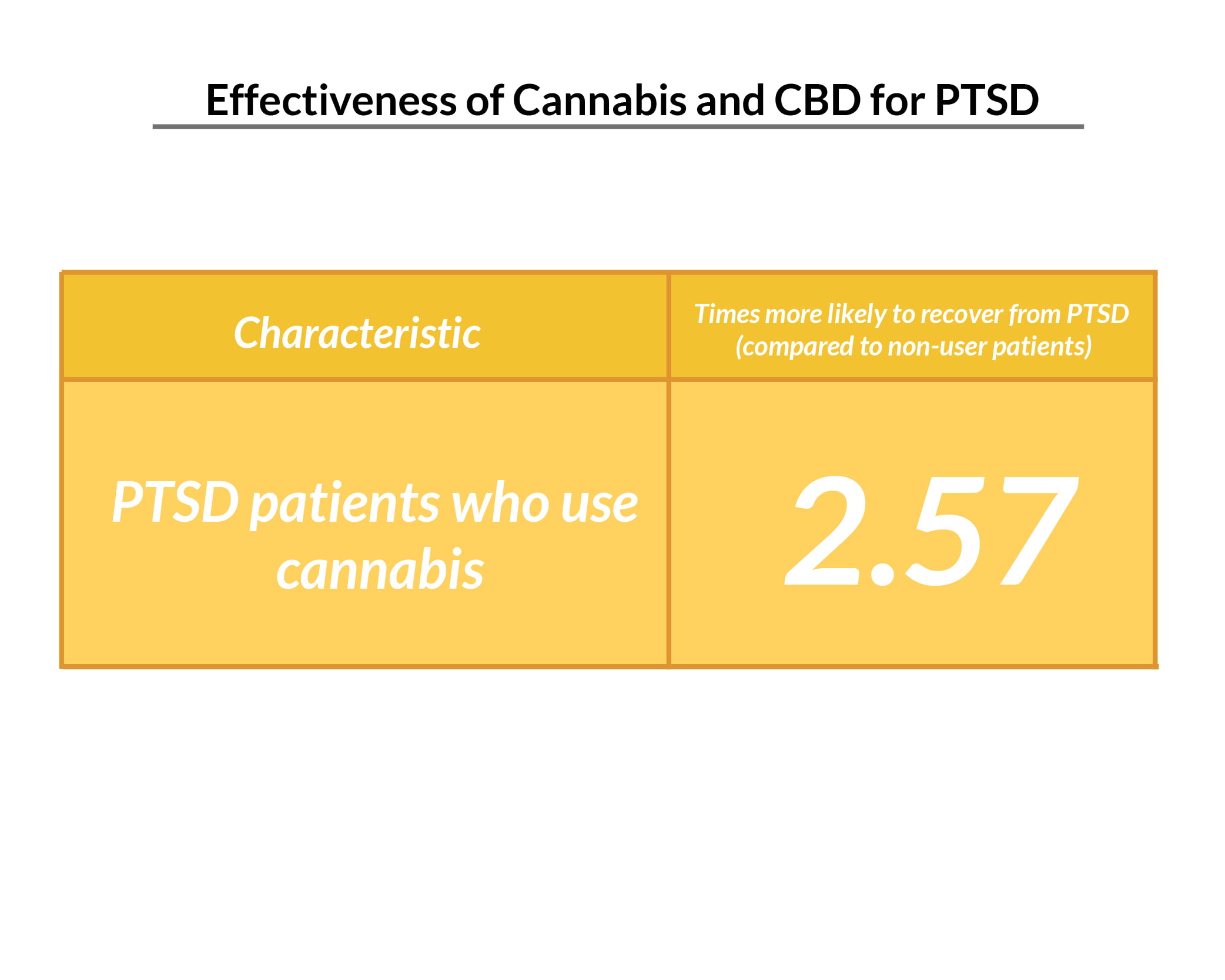

- People with PTSD who use cannabis for their symptoms are 2.57 times more likely to recover from this condition [3].

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as an intense, uncontrollable emotional and physical reaction to a reminder of a traumatic event or distressing memories [4]. This abnormal response to triggers can last for days and even years after the harrowing incident or traumatic event.

How Do You Know If You Have PTSD?

Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder or PTSD include [18]:

- Re-living symptoms: Triggers easily cause flashbacks, intense memories, and terrible nightmares of the incident. These can result in an extreme fight-or-flight response. You experience intense fear and panic attacks. You also develop chest tightness, palpitations, rapid breathing, and increased blood pressure, among others.

- Avoidance symptoms: You avoid places, people, activities, things, and even thoughts and emotions that remind you of the traumatic event.

- Increased arousal symptoms: Small things like loud noises and stressful events can easily startle and rattle you. You feel jittery, nervous, quick to anger, moody, and paranoid. You also develop sleep problems.

- Increased mood and cognition symptoms: You develop negative thoughts and cognitive issues like the inability to focus, concentrate, remember things, or recall memories, especially of the traumatic event. You may also have distorted thoughts and emotions where you blame yourself and feel guilty for what happened.

To be diagnosed with PTSD, you must have [18]:

- At least one symptom of re-experiencing or reliving the traumatic event or incident

- At least one symptom of avoidance

- At least two symptoms of increased reactivity or arousal

- At least two symptoms of cognitive and mood problems

What is the Number One Cause of PTSD?

One of the leading causes of PTSD is sexual violence, and those who experienced sexual trauma have a higher risk of developing PTSD [23].

Who Has the Highest Rate of PTSD?

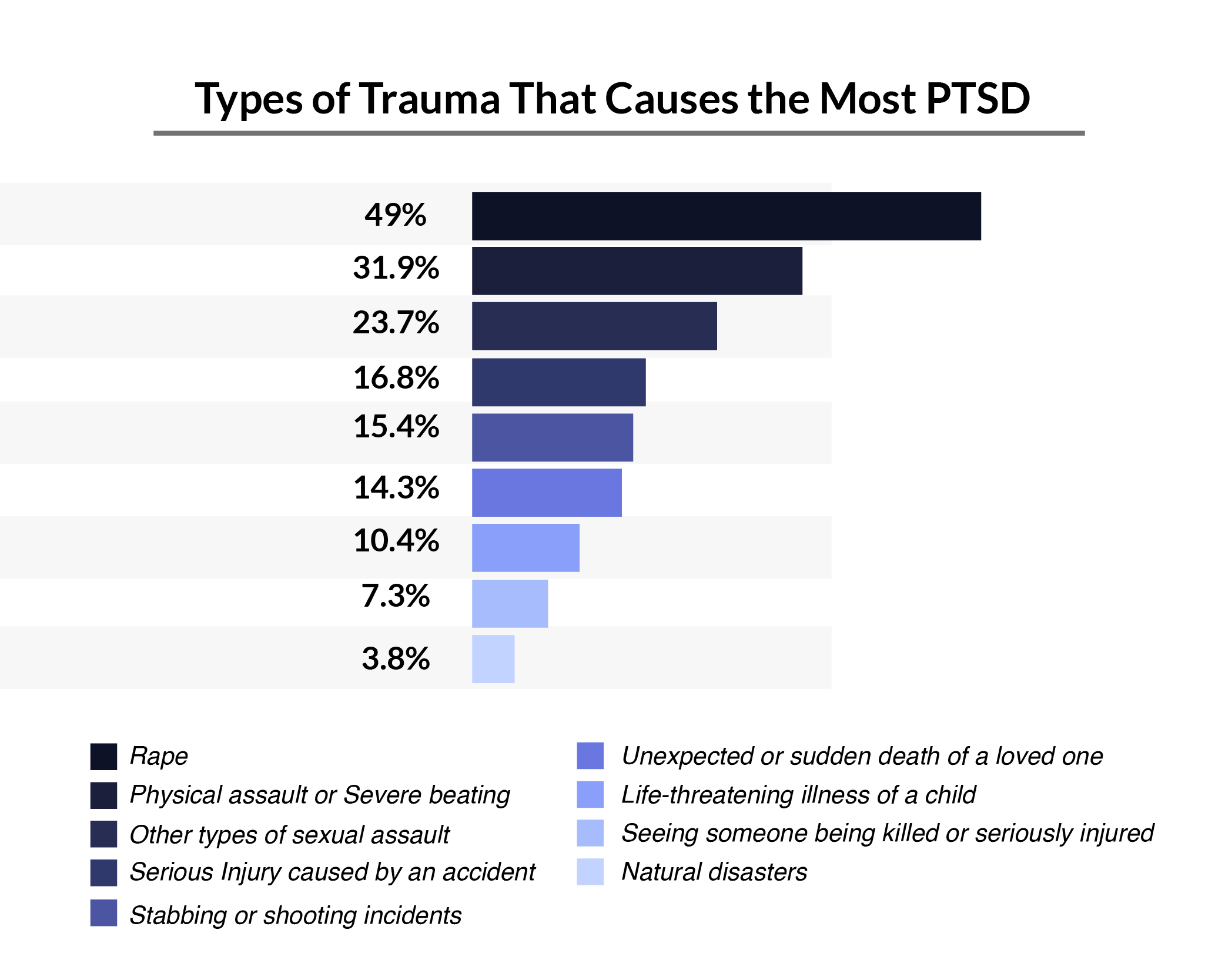

The risks of one developing posttraumatic stress disorder depend on how traumatic the event is.

Of the different traumatic events, rape has the highest PTSD prevalence at 49%, compared to natural disasters at 3.8% [21].

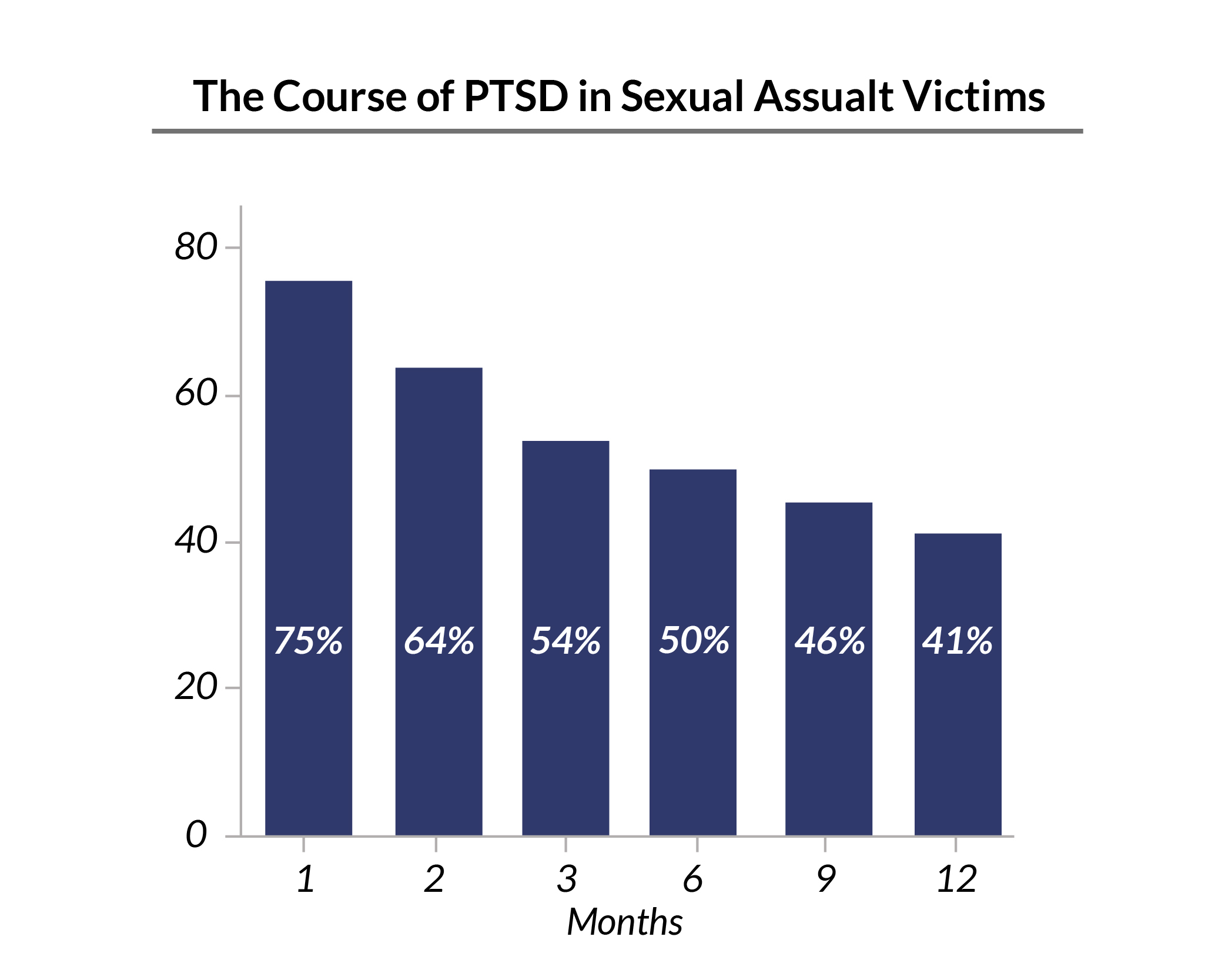

PTSD after rape statistics also show that [28]:

- 94% of women who were raped develop PTSD symptoms during the first two weeks after the traumatic event.

- 30% of them still experience PTSD symptoms nine months after the incident.

- 75% of sexual assault survivors were diagnosed with PTSD a month after the incident. This drops to 54% after three months, and it further drops to 41% after a year [1].

US PTSD Statistics: Who Suffers from PTSD the Most?

According to PTSD statistics:

- 45 to 59-year-old adults are more affected by this mental illness than older adults above 60 years old.

- More women suffer from PTSD than men.

- People in the military are more prone to PTSD than civilians.

What Percent of the Population Has PTSD?

According to the US Department of Veterans Affairs [9]:

- 6% of the American population will have suffered from PTSD at some point in their lives.

- About 12 million American adults suffer from PTSD during any given year.

PTSD is Most Common in Which Age Group?

PTSD is most common among individuals between the ages of 45 and 59 years old at 9.2%, compared to individuals above the age of 60 years old at 2.8% [17].

Among adolescents, about 5% of those between 13 and 17 years old have PTSD [20].

PTSD Male vs Female

Among adolescents, 8% of female adolescents have experienced PTSD in the past year, compared to 2.3% of male adolescents [20].

The lifetime prevalence of PTSD among female adults is 9.7%, compared to 3.6% of male adults [17].

Civilian women have a lifetime prevalence rate of 8%, compared to civilian men at 4.1% [24].

Women veterans have a lifetime prevalence rate of 13.4%, compared to men veterans at 7.7% [24].

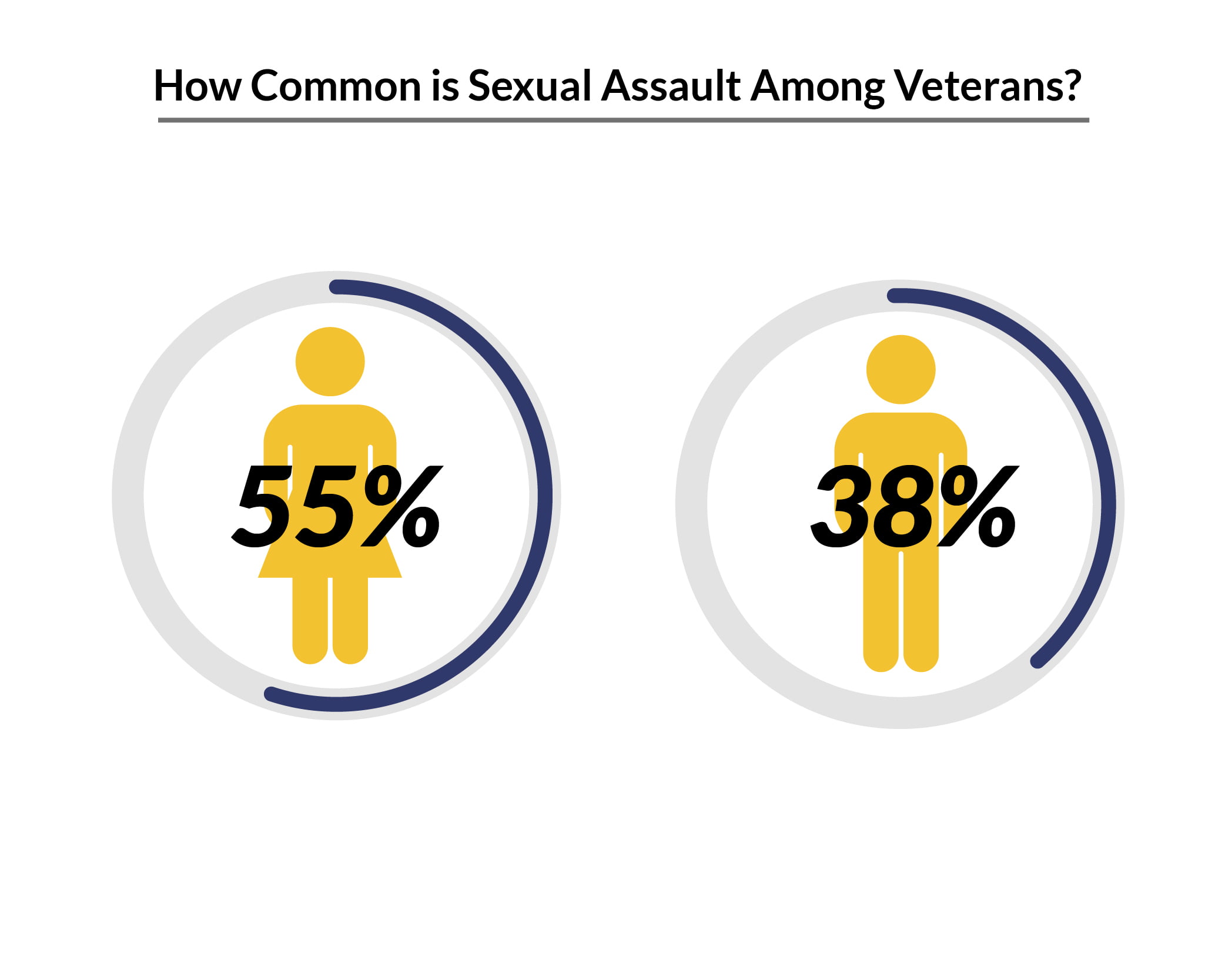

Sexual assault is also high among veterans [9]:

- 55% or 11 out of 20 military women experience sexual harassment during their time in the military, compared to 38% or 19 out of 50 military men.

- 23% or 23 out of 100 military women reported the sexual harassment incident.

PTSD in Veterans Statistics

According to PTSD statistics:

- PTSD prevalence varies depending on the service area.

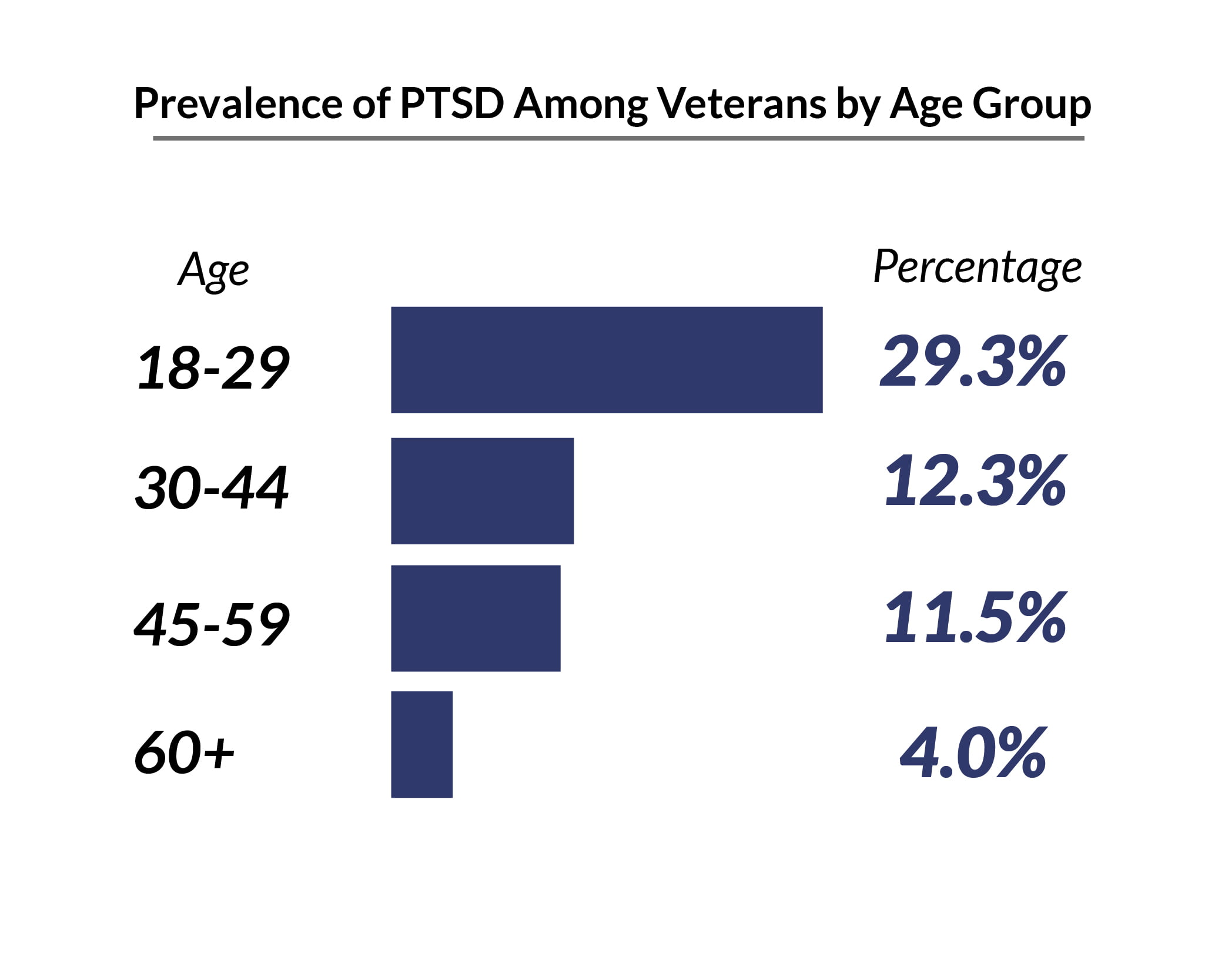

- PTSD is more common among veterans between the ages of 18 and 29 years.

- Veterans have a higher suicide risk than civilians.

How Many Veterans are Affected by PTSD?

11% to 23% of veterans experience PTSD within a given year [2].

The percentage of veterans with PTSD varies depending on their service area, says the Department of Veterans Affairs.

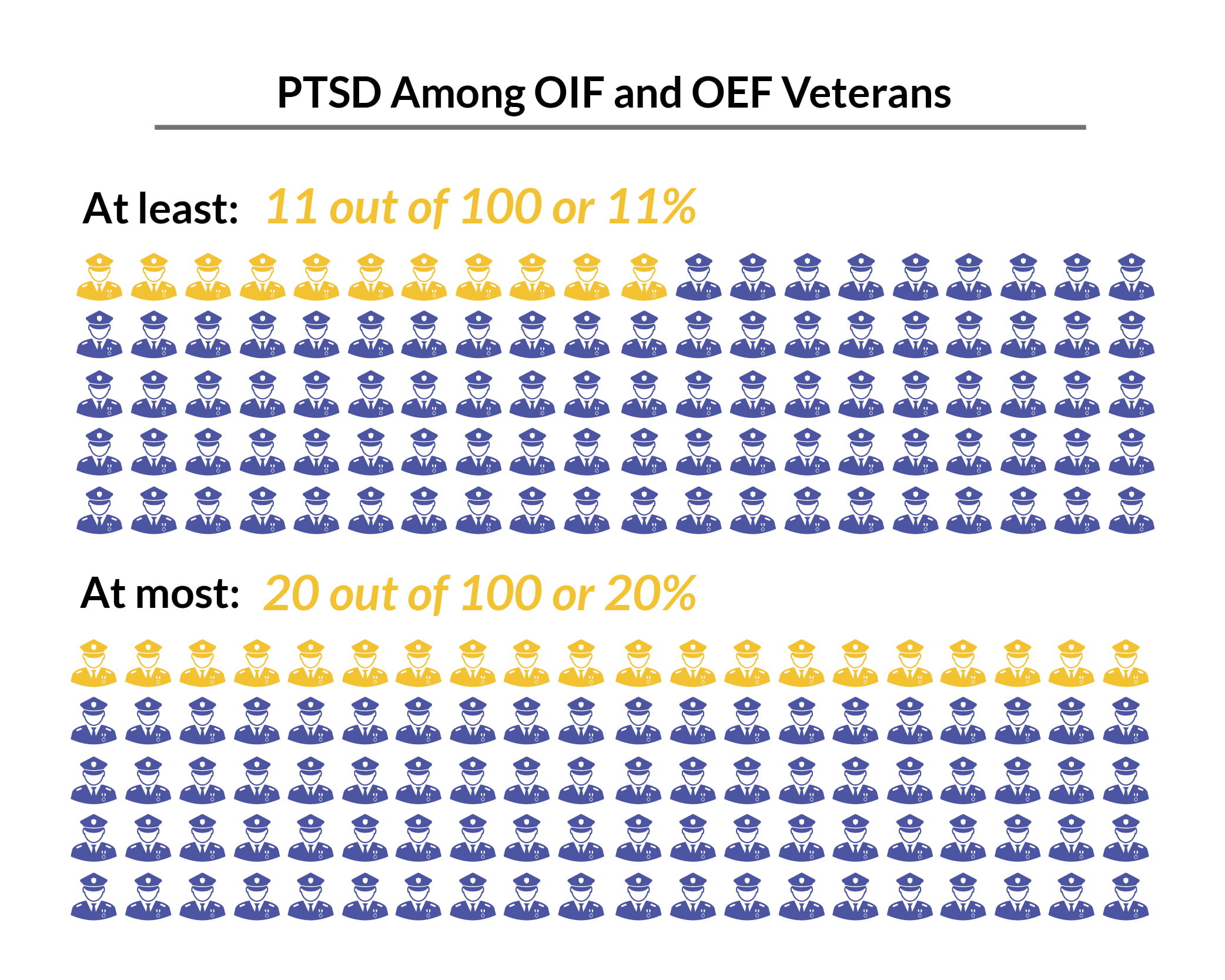

Operations Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Enduring Freedom (OEF):

- About 11% to 20% of veterans have suffered from PTSD in a given year [9].

- Of the 1.9 million veterans, about 209,000 to 380,000 will be developing PTSD, says the Department of Veterans Affairs [27].

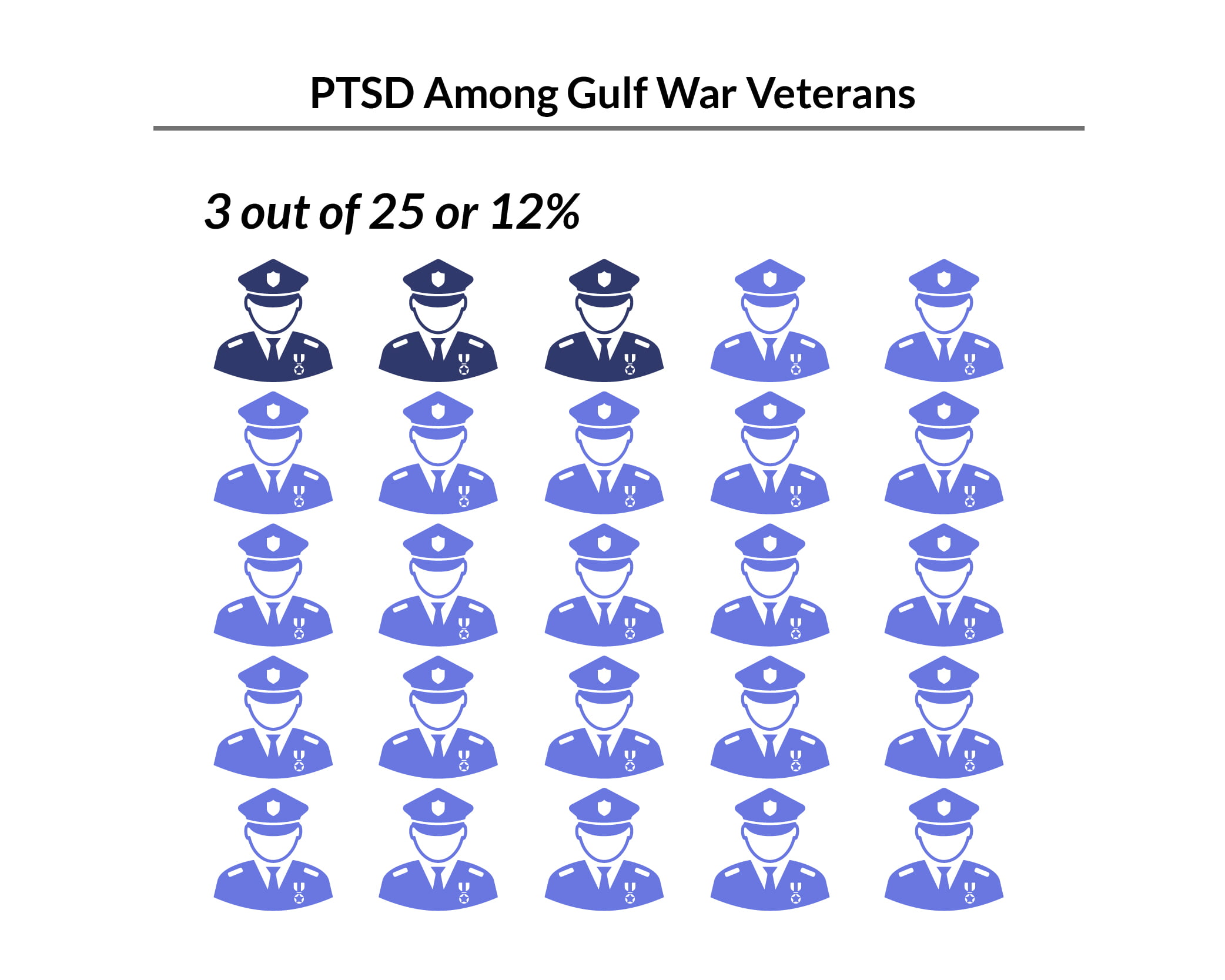

Gulf War (Desert Storm):

- Approximately 12% of veterans have been affected by PTSD in a given year [9].

- Of the 5.5 million American military personnel who served in the area, about 660,000 of them will have developed PTSD [27].

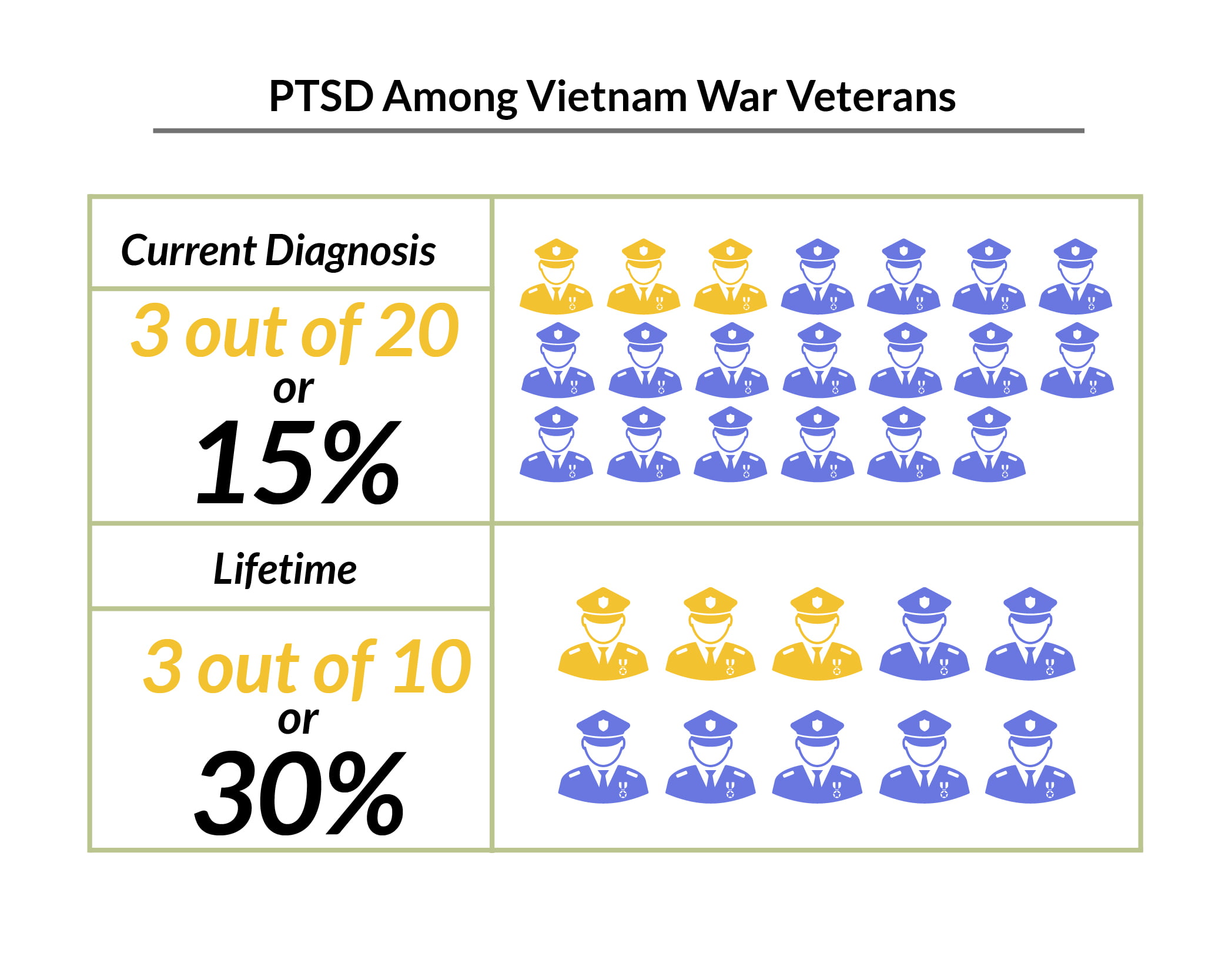

Vietnam War:

- About 15% of veterans have a current diagnosis of PTSD.

- Approximately 30% of veterans have suffered from PTSD in their lifetime [9].

- According to the Department of Veterans Affairs, of the 2.7 million Vietnam veterans, about 810,000 will have developed PTSD [27].

PTSD is more common among military veterans between the ages of 18 and 29 years at 29.3%, compared to veterans over the age of 60 years at 4% [14].

What Does PTSD Do to Veterans?

PTSD statistics military show that veterans with PTSD have a high suicide risk [2]:

- 24.8% or about 1 in 4 veterans have had suicidal thoughts in the past year.

- 69.7% of veterans reported having had suicidal thoughts in the past couple of weeks.

PTSD Treatment for Veterans Statistics

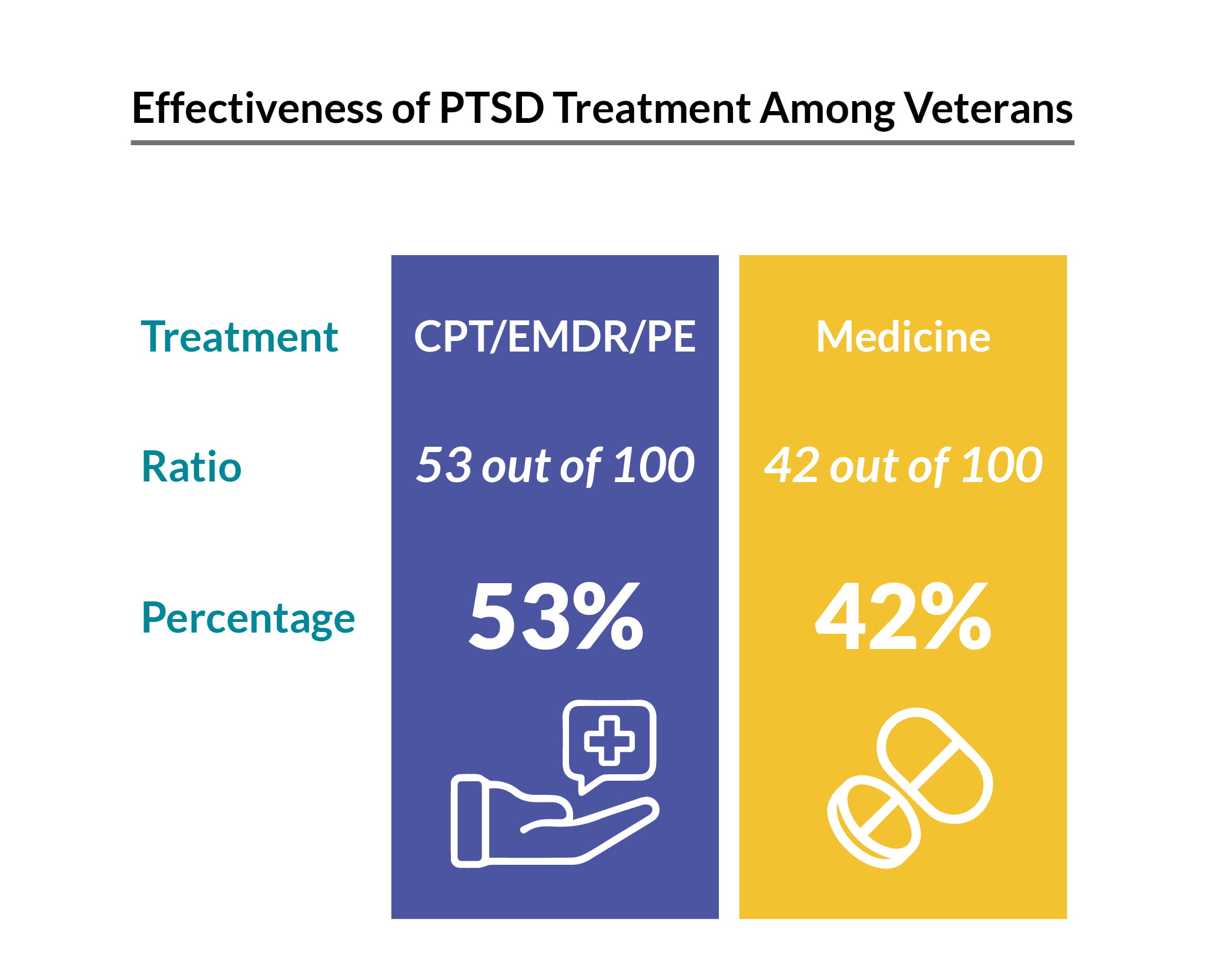

SSRIs for PTSD are prescribed to veterans [22].

- SSRIs had a 60% overall response rate in PTSD patients.

- About 20% to 30% of the patients had complete remission.

- Extended-release venlafaxine had a 78% response rate as well as a 40% remission rate.

Veterans are also given three types of trauma-focused therapy to help with their mental health issues. These are cognitive processing therapy (CPT), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), and prolonged exposure (PE) therapy [19].

A 2021 study also found that about 10 weeks in a military clinic can help improve their mental health issues [15]:

- 38% had significant improvements in their PTSD checklist or PCL.

- 28% of them no longer met the PTSD criteria

- 12.8% of them succeeded.

PTSD in First Responders

First responders’ PTSD statistics show that it’s also very common among American first responders.

- 30% of first responders have mental health problems such as PTSD, compared with the 20% of the general population [6].

- More than 80% of first responders go through traumatic events while on the job [13].

- About 10% to 15% of them have a PTSD diagnosis.

- 400,000 of them have reported some symptoms.

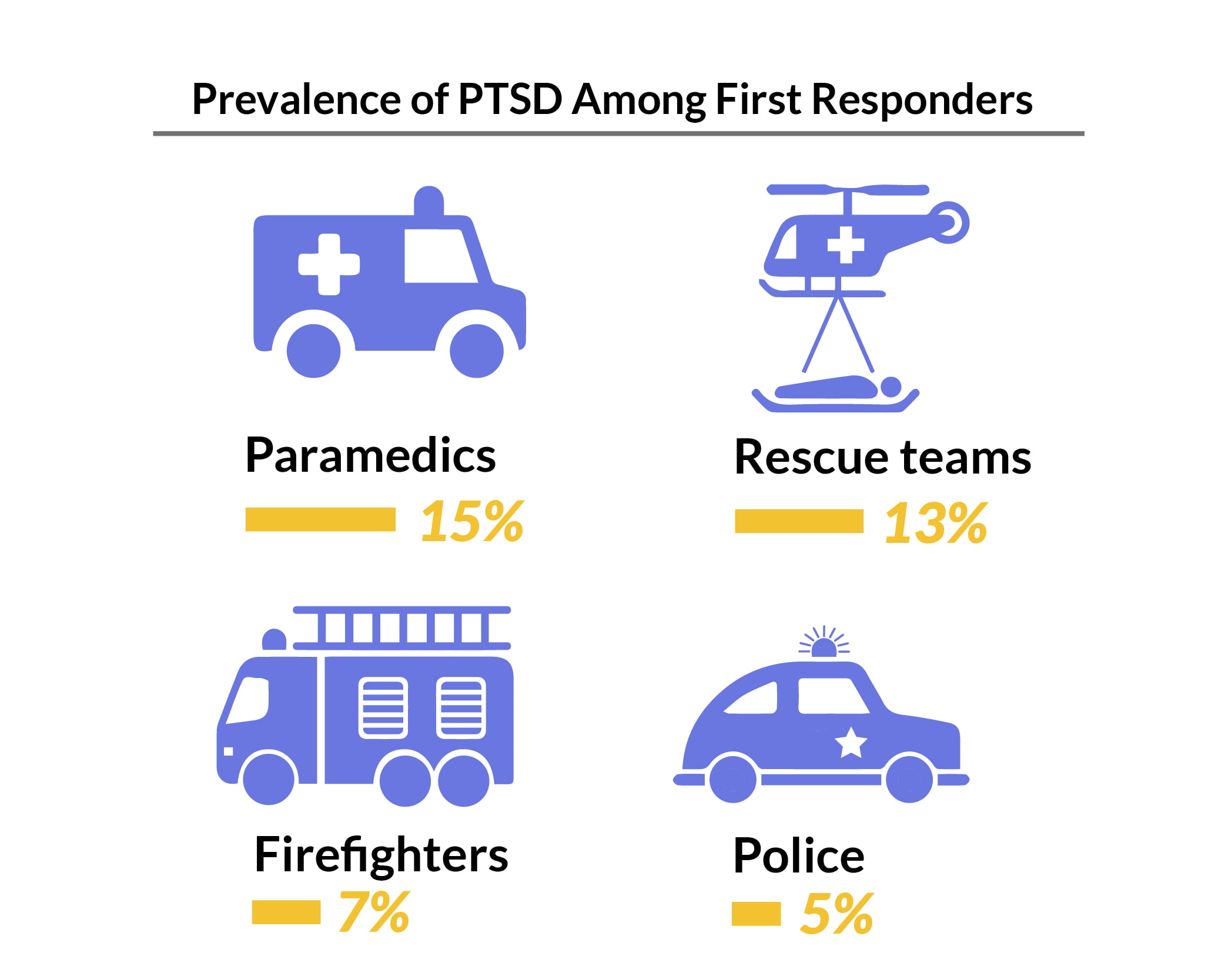

PTSD is highest among emergency personnel at 15%, compared to 5% of police officers [26].

On seeking treatment [10]:

- 57% admit they fear negative repercussions if they sought help.

- 40% say they’re afraid of being demoted or fired if they sought help.

- 7 in 10 say they’d seek treatment more willingly if their organization leader also speaks openly about their own traumatic experiences.

- 8 in 10 say they’d be more encouraged to seek help for their PTSD if a close colleague spoke up.

PTSD Statistics Worldwide

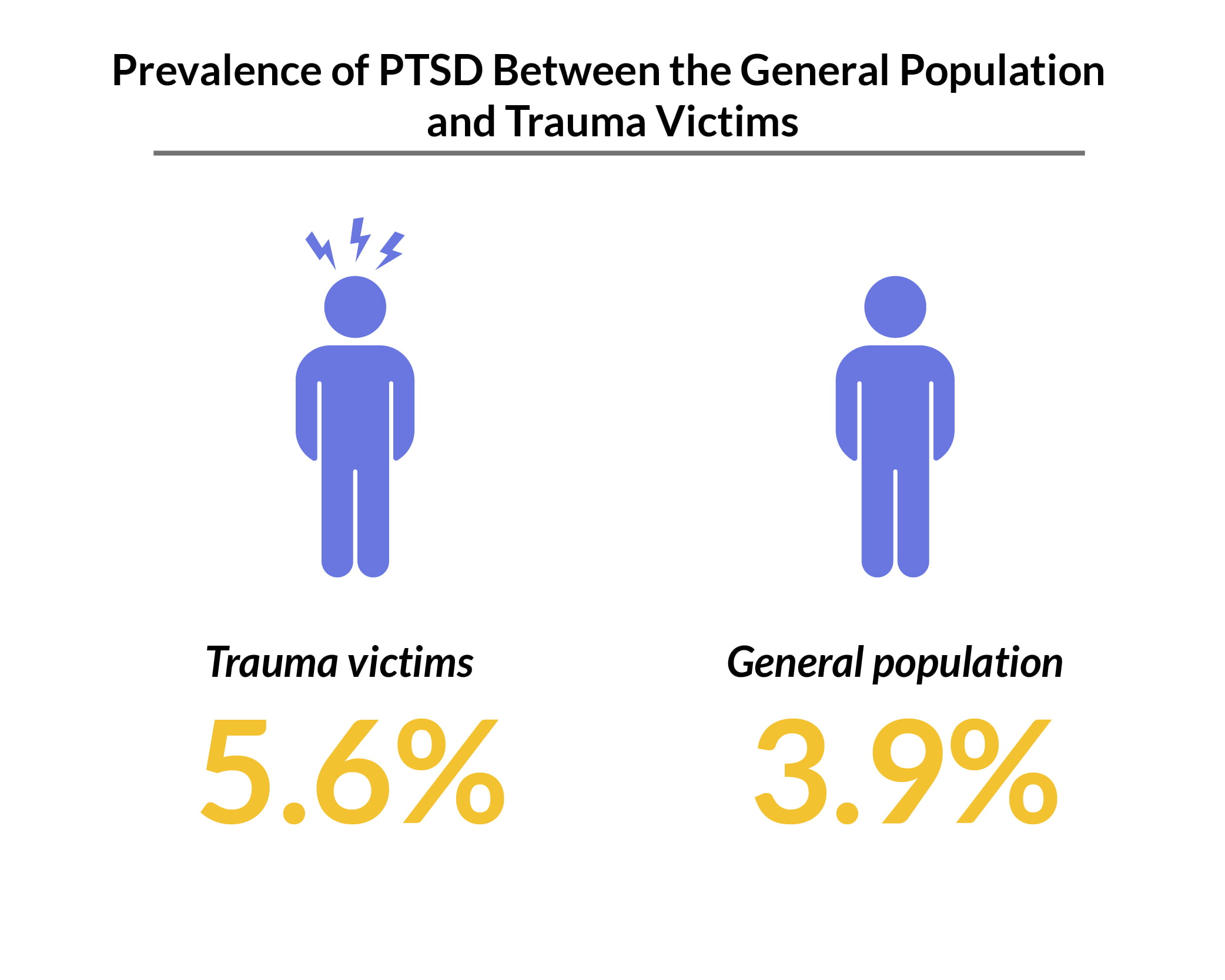

The prevalence of PTSD worldwide is about 3.9% of the general population. In people who had experienced trauma, the prevalence rate is higher at 5.6% [29].

Between 1989 and 2019, about 316 million adult war survivors worldwide had PTSD and/or major depression [8].

- PTSD has a point prevalence rate of 26.51% among people who live in countries or regions affected by war.

- Of those with PTSD, 55.26% also presented with major depression.

PTSD Ukraine War

Wars affect people’s mental health. In Ukraine’s war, for example, even before the 2022 conflict started, Ukrainians were already dealing with PTSD [25].

- According to DSM-5 PTSD criteria, 27.4% of internally-displaced persons or adult IDPs have PTSD.

- According to ICD-11 criteria, PTSD affects 21% of the IDPs in Ukraine.

PTSD Therapy and Treatment

Mental health professionals treat PTSD patients with medications and cognitive behavioral treatment such as exposure therapy, cognition therapy, as well as stress inoculation training.

Medications for PTSD

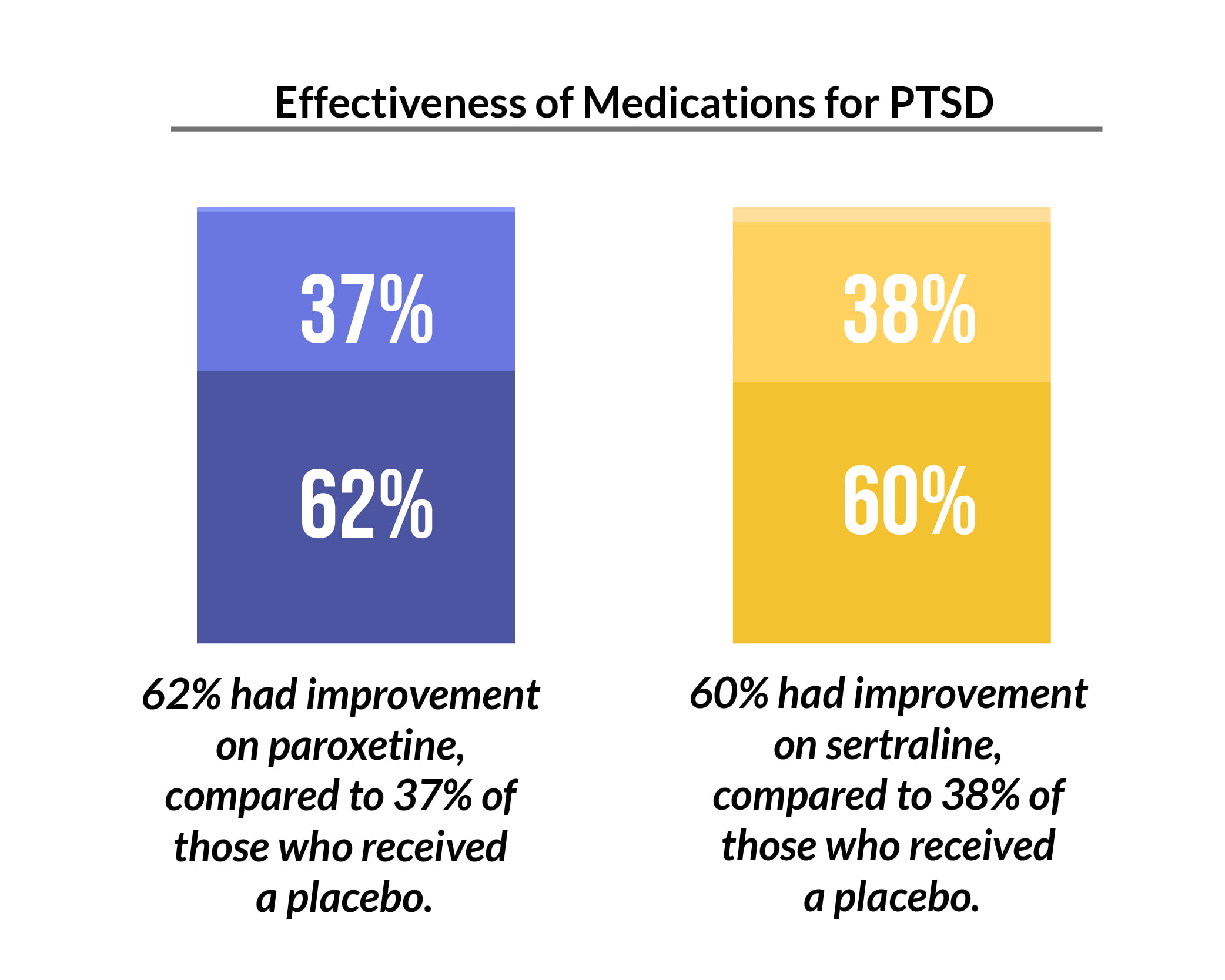

Medications like paroxetine and sertraline are used in treating PTSD. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial [7]:

- Continued sertraline treatment showed a 5% relapse rate, compared to a 26% relapse rate in patients receiving a placebo.

Excluding PTSD medications, researchers studied over a thousand medications. By calculating their incidence rate ratios (IRR), researchers found that 15 of them showed protection associations or strong protective effects on PTSD. Not only did they not increase PTSD risks, but they also reduced the risks by about 30% to more than 50%. These drugs show that their IRRs are biased in the protective direction. The higher the IRR, the more it leans toward the protective direction [11].

- Propranolol: 0.63

- Atomoxetine: 0.64

- Dexmethylphenidate: 0.68

- Dextroamphetamine: 0.73

- Guanfacine: 0.64

- Methylphenidate: 0.65

- Acamprosate: 0.57

- Disulfiram: 0.48

- Naltrexone: 0.55

- Nicotine: 0.63

- Clonidine: 0.65

- Cyproheptadine: 0.60

- Hydroxyzine: 0.65

- Prazosin: 0.33

- Ramelteon: 0.57

Therapy for PTSD

A few weeks of CBT for PTSD may already help reduce symptoms. Several studies show that [7]:

- 21% to 46% of PTSD patients who received CBT within six weeks showed a 50% decrease in the severity of their mental health problems.

- According to a similar study, about 32% to 53% of PTSD patients who received at least 10 CBT sessions had a 50% reduction in the severity of their mental health problems.

- 14% of PTSD patients didn’t continue psychotherapy, with exposure therapy having the highest dropout rate of 50%.

Cannabis and CBD for PTSD

Some PTSD patients also use cannabis and CBD for their symptoms and other mental health disorders.

CBD is a non-psychoactive cannabinoid that cannabis plants produce. Unlike THC which gets you high, CBD won’t induce any psychoactive or mind-altering effects.

- PTSD sufferers who use cannabis are 2.57 times more likely to recover or no longer meet the PTSD criteria than those who are not using cannabis [3].

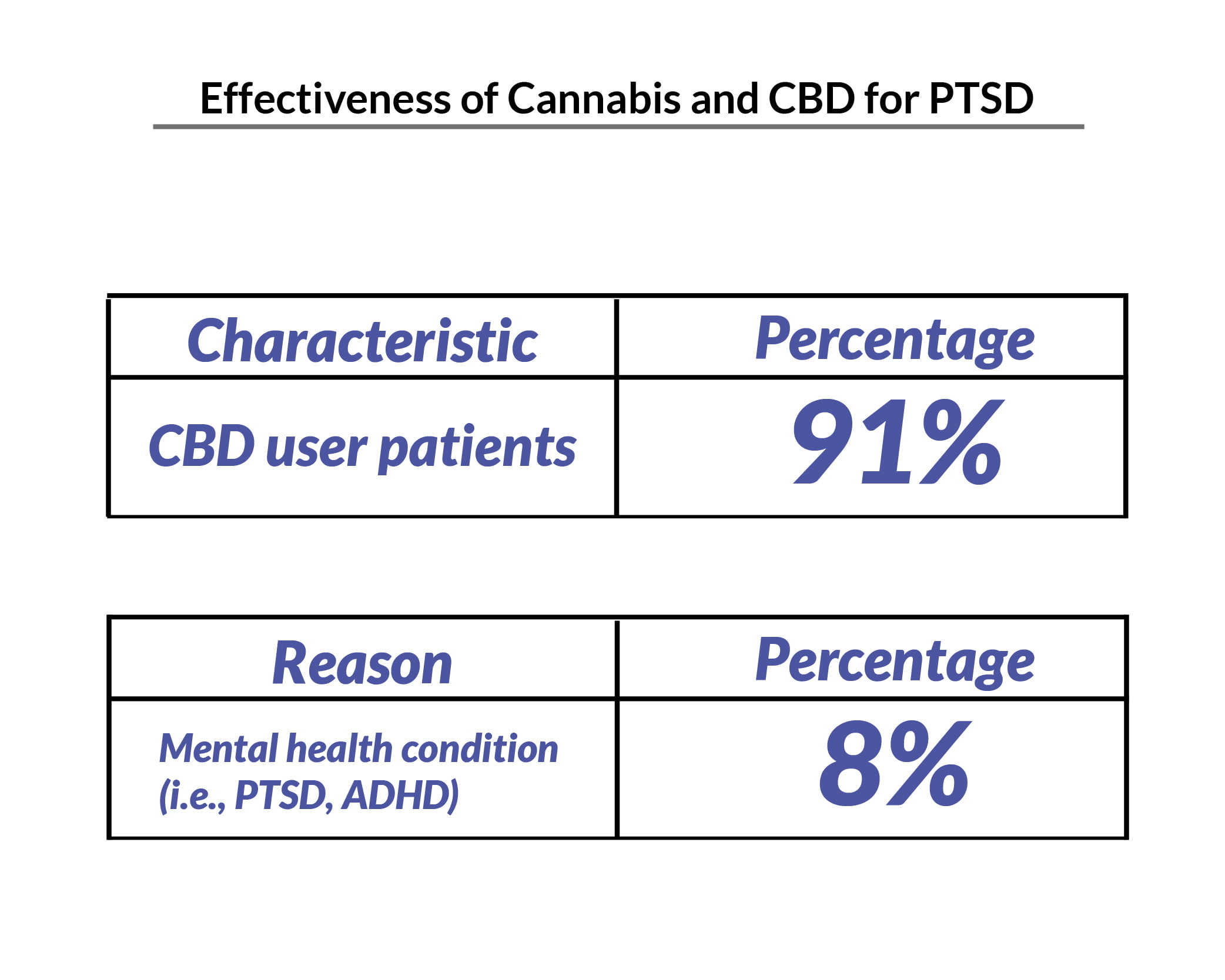

- 91% of the participants in a study on CBD and PTSD showed a reduction in the severity of their PTSD symptoms [5].

- 8% of American adults using CBD say they’re using it for their mental health conditions, including PTSD [16].

Untreated PTSD Statistics and Prognosis

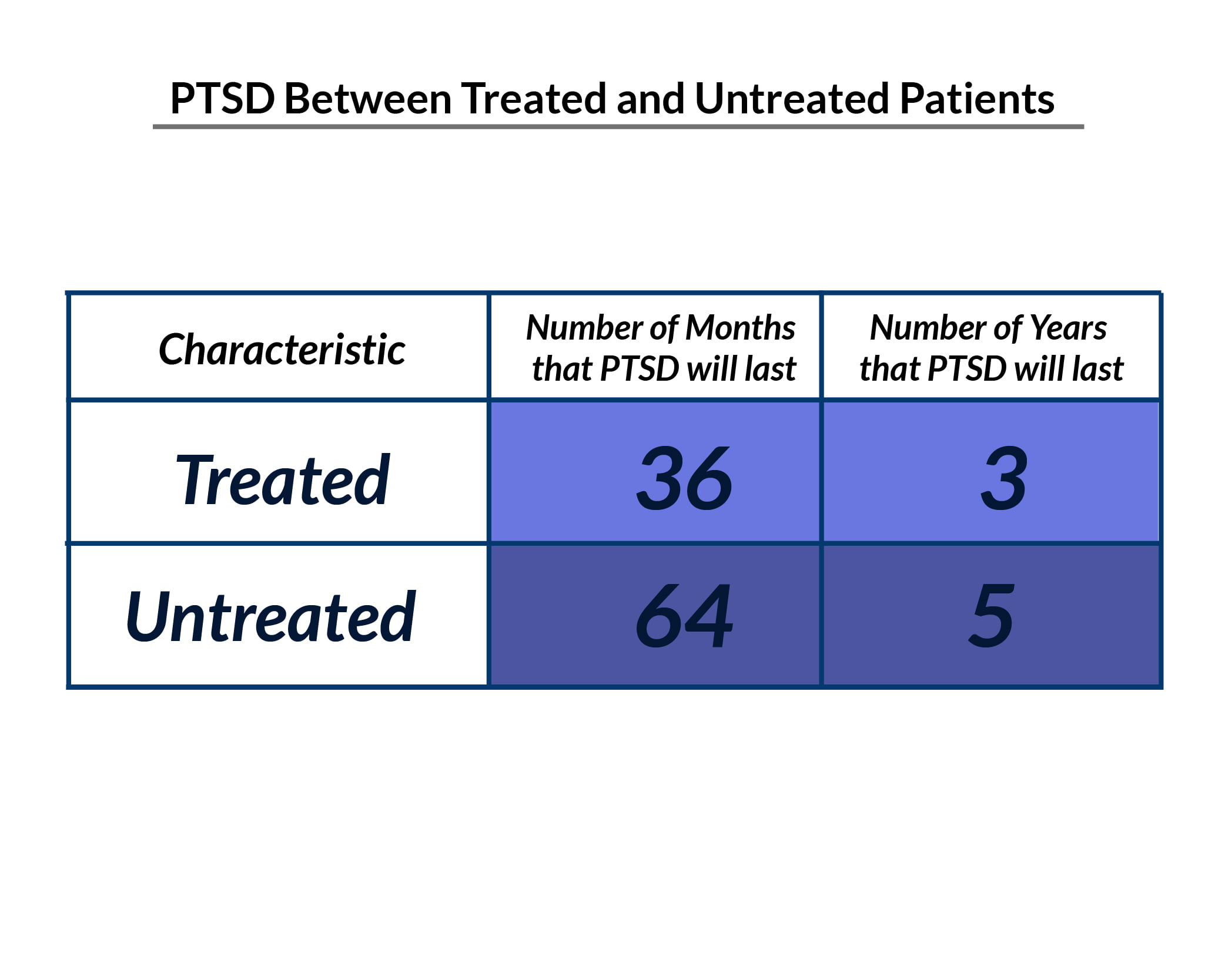

The symptoms of PTSD in people receiving treatment usually last about 36 months. In people not receiving treatment, this can go as long as 64 months [7].

Most PTSD sufferers report significant improvements in the severity of their PTSD symptoms. However, one-third of them never fully recover even with treatment [7].

Conclusion: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Statistics

6% of the general population will have developed PTSD at some point in their lives and 11% to 23% of the veterans will have experienced PTSD within a given year. The leading cause of PTSD is sexual violence at 33%, with women more affected than men by 9.7% and 3.6% respectively.

Cognitive behavioral therapy, talk therapy, and medications help reduce PTSD and other symptoms. Cannabis and CBD may also help in improving their mental health issues.

References

- Bedard-Gilligan, M., Jaffe, A., & Fitzpatrick, N. (2021, July). 75% of sexual assault survivors have PTSD one month later. University of Washington Medicine. [1]

- Berghammer, L., Marx, M. F., Odom, E., & Chisolm, N. (2022). 2021 Annual Warrior Survey, Longitudinal: Wave 1. Wounded Warrior Project. [2]

- Bonn-Miller, M. O., Brunstetter, M., Simonian, A., Loflin, M. J., Vandrey, R., Babson, K. A., & Wortzel, H. (2022). The Long-Term, Prospective, Therapeutic Impact of Cannabis on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, 7(2), 214–223. [3]

- Coping with a Traumatic Event. (2003). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [4]

- Elms, L., Shannon, S., Hughes, S., & Lewis, N. (2019). Cannabidiol in the Treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Case Series. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 25(4), 392–397. [5]

- First Responders: Behavioral Health Concerns, Emergency Response, and Trauma. (2018, May). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). [6]

- Grinage, B. D. (2003, December 15). Diagnosis and Management of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. American Academy of Family Physicians. [7]

- Hoppen, T. H., Priebe, S., Vetter, I., & Morina, N. (2021). Global burden of post-traumatic stress disorder and major depression in countries affected by war between 1989 and 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Global Health, 6(7), e006303. [8]

- How Common is PTSD in Adults? – PTSD: National Center for PTSD. (2022). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. [9]

- Kennedy-Hansen, H. (2020, November). How employers can help first responders stay mentally and emotionally strong. Kaiser Permanente. [10]

- Kern, D. M., Teneralli, R. E., Flores, C. M., Wittenberg, G. M., Gilbert, J. P., & Cepeda, M. S. (2022). Revealing Unknown Benefits of Existing Medications to Aid the Discovery of New Treatments for Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder. Psychiatric Research and Clinical Practice, 4(1), 12–20. [11]

- Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593. [12]

- Klimley, K. E., van Hasselt, V. B., & Stripling, A. M. (2018). Posttraumatic stress disorder in police, firefighters, and emergency dispatchers. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 43, 33–44. [13]

- Lee, L. (2019). PTSD and Aging. National Center for PTSD, 30(4), 1050–1835. [14]

- Mclay, R., Fesperman, S., Webb-Murphy, J., Delaney, E., Ram, V., Nebeker, B., & Burce, C. M. (2021). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Treatment Outcomes in Military Clinics. Military Medicine. [15]

- Mikulic, M. (2020, December). Leading reasons why U.S. adults use cannabidiol as of 2020. Statista. [16]

- National Comorbidity Survey. (2007). Harvard Medical School. [17]

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. (2008). The National Institute of Mental Health. [18]

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). (2022). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. [19]

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Facts And Statistics. (2021, April). Vertava Health. [20]

- PTSD Risks or Risks of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. (2015). PTSD Alliance. [21]

- Reisman, M. (2016). PTSD Treatment for Veterans: What’s Working, What’s New, and What’s Next. P & T: A Peer-Reviewed Journal for Formulary Management, 41(10), 623–634. [22]

- Sareen, J. (2022). Posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, course, assessment, and diagnosis. UpToDate. [23]

- Schein, J., Houle, C., Urganus, A., Cloutier, M., Patterson-Lomba, O., Wang, Y., King, S., Levinson, W., Guérin, A., Lefebvre, P., & Davis, L. L. (2021). Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States: a systematic literature review. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 37(12), 2151–2161. [24]

- Shevlin, M., Hyland, P., Vallières, F., Bisson, J., Makhashvili, N., Javakhishvili, J., Shpiker, M., & Roberts, B. (2017). A comparison of DSM-5 and ICD-11 PTSD prevalence, comorbidity, and disability: an analysis of the Ukrainian Internally Displaced Person’s Mental Health Survey. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 137(2), 138–147. [25]

- Torchalla, I., & Strehlau, V. (2017). The Evidence Base for Interventions Targeting Individuals With Work-Related PTSD: A Systematic Review and Recommendations. Behavior Modification, 42(2), 273–303. [26]

- Veteran PTSD Statistics That Everyone Should Know. (2020, March). Heroes’ Mile. [27]

- Victims of Sexual Violence: Statistics. (2016). RAINN. [28]

- Worldwide prevalence of PTSD. (2021, October). NeuRA Library. [29]